Received also with gratitude, though the bridge it provides is purely fortuitous—and fortunate—is Claude Wilkinson’s “Anything That Floats,” New Orleans being the heart of the final essay in the series known as “Notes on the State of Southern Poetry,” “Controversies, Connections, and Coincidences”:

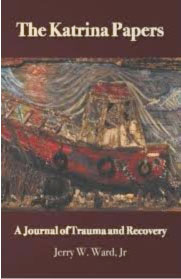

Before even opening The Katrina Papers by Jerry Ward, its cover art ferries us toward the book’s thematic and metaphoric heart. Herbert Kearney’s construction All Mothers Are Boats is composed of paint, driftwood, lumber, dirt, masonry, and other rubble found around the artist’s studio post-Katrina. The literal importance of boats during and after the hurricane is evoked by the image alone. However, as we soon find out, Ward’s very act of writing a journal was for the author, a means of survival. His introduction refers to Katrina as “a matrix of stories,” and indeed whether speaking of the storm or the journal, there are situations within which something else originates, develops, or is contained. Although the book is in part documentary of a cataclysmic event, design elements such as no table of contents and the use of varied fonts and forms throughout the text remind us that The Katrina Papers is in fact one man’s memoir.

Before even opening The Katrina Papers by Jerry Ward, its cover art ferries us toward the book’s thematic and metaphoric heart. Herbert Kearney’s construction All Mothers Are Boats is composed of paint, driftwood, lumber, dirt, masonry, and other rubble found around the artist’s studio post-Katrina. The literal importance of boats during and after the hurricane is evoked by the image alone. However, as we soon find out, Ward’s very act of writing a journal was for the author, a means of survival. His introduction refers to Katrina as “a matrix of stories,” and indeed whether speaking of the storm or the journal, there are situations within which something else originates, develops, or is contained. Although the book is in part documentary of a cataclysmic event, design elements such as no table of contents and the use of varied fonts and forms throughout the text remind us that The Katrina Papers is in fact one man’s memoir.

Generally sequential in its arrangement, the book begins under the romantic heading Early September Preludes. Ward’s first entry on September 2, 2005 sets out, “Being in the First Baptist Church shelter means . . . damn, the words don’t want to come out of the pencil . . . that thousands of us have been abused by Nature and revenge is impossible” (11). As one might expect of such writing, Ward’s iteration of the importance of home and the force of loss is constant. Considering his own transformation even near the end of the journal, the author thinks to himself and then writes,

You are fooling yourself about bright moments. All moments from now until the time of your dying shall be dull and prickly. You shall laugh, and laughter will bring you no joy. Sadness shall season all your waking minutes. Peace will exist when you are asleep. You will never be conscious of it. Stop wishing and dreaming. Wake up. (202-03)

What readers may not expect however, is Ward’s sometimes humorous, often Zen observations and his continued professional engagement in the face of catastrophe. At one point he asks, “Does water walk when you swim?” (210). Six days earlier, Ward expresses his annoyance over a fellow juror’s tardiness in making a selection regarding a literary award.

The Katrina Papers also presents the Zeitgeist of Ward’s vexing trial of registering online with FEMA and his reflections on the joy of getting a much needed haircut, as well as vacillating, conflicting emotions—from the brief happiness of finding out via e-mails that friends and family are still alive to the sorrow of his situation. “Be happy, then be miserable,” he writes (11). Interspersed in the entries are associations that Ward makes between experiences such as watching telecasts of people struggling through the flood and his having edited a poetry anthology subtitled Wade in the Water, followed by the mimetically iambic thought, “A boat is anything that floats” (11).

The Katrina Papers also presents the Zeitgeist of Ward’s vexing trial of registering online with FEMA and his reflections on the joy of getting a much needed haircut, as well as vacillating, conflicting emotions—from the brief happiness of finding out via e-mails that friends and family are still alive to the sorrow of his situation. “Be happy, then be miserable,” he writes (11). Interspersed in the entries are associations that Ward makes between experiences such as watching telecasts of people struggling through the flood and his having edited a poetry anthology subtitled Wade in the Water, followed by the mimetically iambic thought, “A boat is anything that floats” (11).

Ward’s claim of “trauma affect[ing] the mind, the soul, the body” is buoyed by descriptions of “wading in poisoned water with snakes and the dead bodies of animals and people floating by” (12). Although certain entries vent anger through commonly voiced political stabs at the American military’s involvement in Iraq by suggesting that the true terrorism is here in the flooded coastal areas, The Katrina Papers is also a stocktaking of sorts. Under the heading You Don’t Know What It Means, Ward describes the awful task of preparing to abandon one’s most secure place in the world, possibly never to return: “You hurriedly pack—vital documents, granola bars and water, sports clothing and toiletries for a week, put on your Army dog tags for good luck,” reminding himself “[You did survive Vietnam], lock up the house and leave at 12:06 with a backward glance at John Scott’s ‘Spirit House’ on the corner of St. Bernard and Gentilly (13).

Yet in the scope of other atrocities such as 9/11, slavery, and “the AIDS/famine/ethnic laundering crises in Africa and the triumph of evil elsewhere,” the author ultimately considers himself blessed (13). Nevertheless, Ward, a Richard Wright scholar, poet, and English professor, remembers and clings to sundry safety nets, stating: “You do have unfinished work at Dillard University, and suicide, damning your Roman Catholic soul, would hurt the relatives who love you. Wear the mask. Smile. Pretend you do not hurt” (13). The journal is evidence of an unquenched desire to ruminate on Emersonian philosophy and Harold Pinter’s Nobel Prize speech, to read new works of literary theory, and to communicate with colleagues. Alongside Ward’s Olympian pursuits are his mundane but necessary lists reminding him to write checks for bills and file a claim for flood insurance.

Yet in the scope of other atrocities such as 9/11, slavery, and “the AIDS/famine/ethnic laundering crises in Africa and the triumph of evil elsewhere,” the author ultimately considers himself blessed (13). Nevertheless, Ward, a Richard Wright scholar, poet, and English professor, remembers and clings to sundry safety nets, stating: “You do have unfinished work at Dillard University, and suicide, damning your Roman Catholic soul, would hurt the relatives who love you. Wear the mask. Smile. Pretend you do not hurt” (13). The journal is evidence of an unquenched desire to ruminate on Emersonian philosophy and Harold Pinter’s Nobel Prize speech, to read new works of literary theory, and to communicate with colleagues. Alongside Ward’s Olympian pursuits are his mundane but necessary lists reminding him to write checks for bills and file a claim for flood insurance.

Near the anniversary of his leaving New Orleans just before Katrina hit, the author recalls other personal traumatic events—namely the death of his father on December 25, 1957, which hence hardened him against any celebration of Christmas. On the death of his mother in April 1992, which he admits to being better able to handle, Ward writes, “By then I had experienced the rising and falling rhythms of life”—an ominous, apt segue to the coming storm (232). Thus the journal closes in a manner reminiscent of an absurdist play. Exclaimed in bold font are the directions—which I ask you, dear Readers, to follow with me on 29 August 2012, the seventh anniversary of Katrina’s landfall:

falling rhythms of life”—an ominous, apt segue to the coming storm (232). Thus the journal closes in a manner reminiscent of an absurdist play. Exclaimed in bold font are the directions—which I ask you, dear Readers, to follow with me on 29 August 2012, the seventh anniversary of Katrina’s landfall:

Yet in the scope of other atrocities such as 9/11, slavery, and “the AIDS/famine/ethnic laundering crises in Africa and the triumph of evil elsewhere,” the author ultimately considers himself blessed (13). Nevertheless, Ward, a Richard Wright scholar, poet, and English professor, remembers and clings to sundry safety nets, stating: “You do have unfinished work at Dillard University, and suicide, damning your Roman Catholic soul, would hurt the relatives who love you. Wear the mask. Smile. Pretend you do not hurt” (13). The journal is evidence of an unquenched desire to ruminate on Emersonian philosophy and Harold Pinter’s Nobel Prize speech, to read new works of literary theory, and to communicate with colleagues. Alongside Ward’s Olympian pursuits are his mundane but necessary lists reminding him to write checks for bills and file a claim for flood insurance.

Yet in the scope of other atrocities such as 9/11, slavery, and “the AIDS/famine/ethnic laundering crises in Africa and the triumph of evil elsewhere,” the author ultimately considers himself blessed (13). Nevertheless, Ward, a Richard Wright scholar, poet, and English professor, remembers and clings to sundry safety nets, stating: “You do have unfinished work at Dillard University, and suicide, damning your Roman Catholic soul, would hurt the relatives who love you. Wear the mask. Smile. Pretend you do not hurt” (13). The journal is evidence of an unquenched desire to ruminate on Emersonian philosophy and Harold Pinter’s Nobel Prize speech, to read new works of literary theory, and to communicate with colleagues. Alongside Ward’s Olympian pursuits are his mundane but necessary lists reminding him to write checks for bills and file a claim for flood insurance.Near the anniversary of his leaving New Orleans just before Katrina hit, the author recalls other personal traumatic events—namely the death of his father on December 25, 1957, which hence hardened him against any celebration of Christmas. On the death of his mother in April 1992, which he admits to being better able to handle, Ward writes, “By then I had experienced the rising and

falling rhythms of life”—an ominous, apt segue to the coming storm (232). Thus the journal closes in a manner reminiscent of an absurdist play. Exclaimed in bold font are the directions—which I ask you, dear Readers, to follow with me on 29 August 2012, the seventh anniversary of Katrina’s landfall:

falling rhythms of life”—an ominous, apt segue to the coming storm (232). Thus the journal closes in a manner reminiscent of an absurdist play. Exclaimed in bold font are the directions—which I ask you, dear Readers, to follow with me on 29 August 2012, the seventh anniversary of Katrina’s landfall:

Work Cited

Ward, Jerry W., Jr. The Katrina Papers: A Journal of Trauma and Recovery. New Orleans: U of New Orleans P, 2008.

Ward, Jerry W., Jr. The Katrina Papers: A Journal of Trauma and Recovery. New Orleans: U of New Orleans P, 2008.

080112 1323

No comments:

Post a Comment